Do expressions of gratitude make online communities stronger and more welcoming? Or is it a mistake when communities try to sustain themselves with virtual, symbolic tokens? Might the answers to these questions vary between cultures?

When the Wikimedia Foundation (WMF) developed software for sharing appreciation in 2011, many Wikipedians were already thanking and encouraging each other. The foundation had heard from editors that their motivations depended on how they believed other editors viewed them as a person. So the foundation created WikiLove, a way to express appreciation for others when browsing profile pages.

Since then, editors have sent each other WikiLove in the form of baklava, kittens, croissants, goats, barnstars, along with encouraging messages. To support even more appreciation between Wikipedians, the Editor Engagement Team also created a “Thanks” feature in 2013 that allows editors to thank someone for a specific contribution they made to Wikipedia.

To discover the impact of appreciation among Wikipedians, CivilServant (incubated by GlobalVoices) is beginning to partner with several non-English language communities to test the effects of software for giving and receiving recognition. To prepare for that research, we collected the full historical describing how WikiLove and Thanks are used across the many languages and cultures of Wikipedia (we have published the full code and data from this project).

In this post, we share four things we learned about appreciation on Wikipedia from this data. We also describe how we hope to work with Wikipedia's language communities. If you have ideas and would like us to work with Wikipedia in your language, please contact us!

Why Appreciation Matters

Why is appreciation significant, and what might it mean for someone on Wikipedia? After researchers found that randomly giving editors awards increased productivity in English Wikipedia (here and here), many people proposed “gamifying” Wikipedia. In this view, if Wikipedians are given symbolic rewards and status symbols, they might do more work without the cost of anyone relating to them as people. Other online communities, including Global Voices, have asked similar questions.

Public attitudes are now shifting about these gamification techniques– what anthropologists call behavioral traps. Many people now feel cheated by companies who people say manipulated their behavior without offering something meaningful in return. Who is right?

Both may be right. Appreciation is more than just giving someone a reward. It plays a complex role in our motivations and our relationships with others. When someone thanks another person, it's an exchange between people, and it can imply an obligation to help them in the future. Because gratitude connects people, it is one of the forces that tie communities together. Appreciation can sometimes be used to create exclusive groups or, the opposite, to broaden circles of participation. It is also related to how we feel about ourselves; stories of gratitude are one way people manage life's problems. As Nathan and his colleagues found in past research at a large company, appreciation tools might sometimes take these complex, strong networks between people and change their meaning into something unsatisfying. Could this happen on Wikipedia?

On Wikipedia, what are the effects of appreciation on people's participation, their connectedness to others, and their beliefs about how other people see them? Ever since Nathan and his colleagues first analyzed WikiLove and Thanks in 2014, we have heard from editors at multiple language wikis who want to find out. When CivilServant received grant funding to develop behavioral studies together with Wikipedians in various languages, we immediately thought about WikiLove and Thanks. In our conversations with editors, many people shared personal stories about the positive impact of Thanks, and others expressed doubt that WikiLove and Thanks matter to people. Wikipedians’ curiosity about the effects of Thanks and Love make them good candidates for further research.

Inspired by these conversations, the team at CivilServant is working with Wikipedians to learn more. This summer, we downloaded the full history of Thanks and WikiLove from July 2011 through June 2018 across 27 Wikipedias–a total of over 3.8 million exchanges. Here are some of the things we learned.

How Common is Appreciation on Wikipedia?

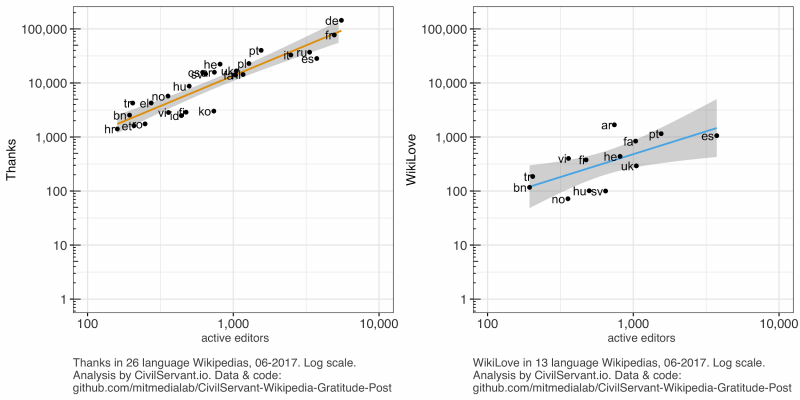

Over seven years, roughly 280 thousand user accounts in those 27 Wikipedias have sent at least one message of appreciation to 300 thousand other people. Nearly half of the accounts that send and receive appreciation are outside of the English Wikipedia– languages that we focus on in this post. While people exchange more appreciation on languages with more activity, Wikipedians in some languages (such as Arabic) use both features more than a simple model would expect from the number of active editors.

Comparing Thanks and WikiLove

Comparing these two charts, we also see that Thanks is more common than WikiLove on Wikipedias that offer both options. On average, communities give 43 times more thanks than love. Why might that be? Wikipedians have explained that it's much easier to click a single link to send Thanks than to choose a picture and write someone a personal message (WikiLove).

While Thanks is easier to use, is Thanks as influential or meaningful to people as WikiLove? That is one question we might ask through the experiments that we're designing together with Wikipedians.

Who Gives and Receives Appreciation on Wikipedia?

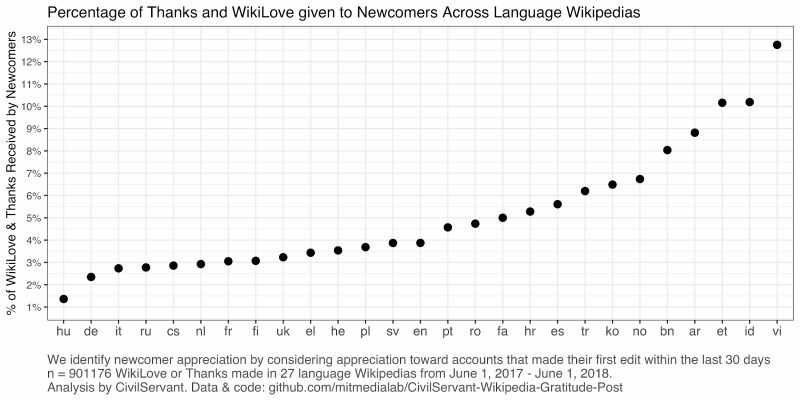

While some communities use Thanks and WikiLove to welcome newcomers, others send appreciation primarily to more experienced Wikipedians. To find out, we made a chart that shows the percentage of WikiLove and Thanks given to newcomers in the year leading up to June 1, 2018. People in three languages sent more than 10% of all Thanks and WikiLove to newcomers in that period. In contrast, five other languages sent less than 3% of their appreciation to newcomers.

These differences make us wonder if different languages and cultures might use and experience appreciation differently– something that we might learn from the results of our future experiments with different language Wikipedias.

Do People Give and Receive Similar Amounts of Appreciation?

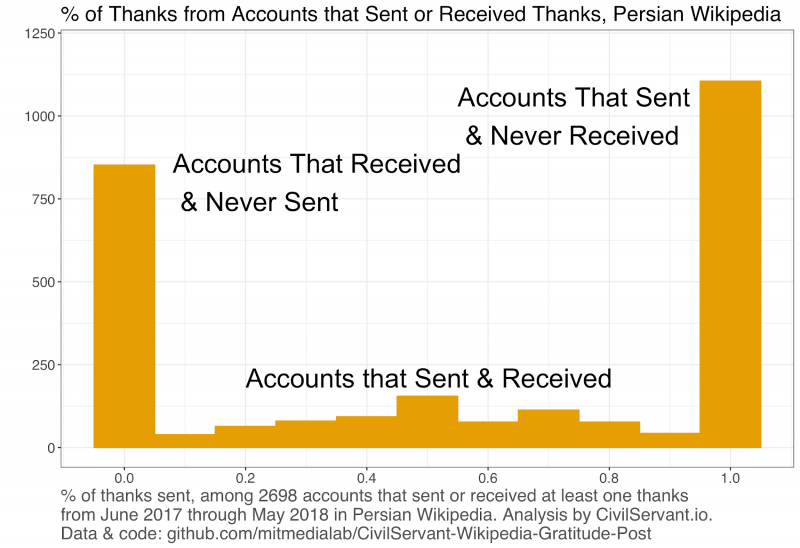

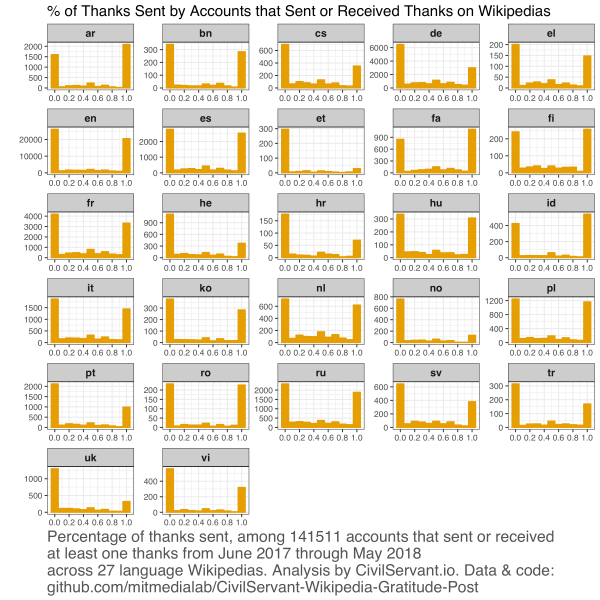

Do people share as much appreciation as they receive, and do different people tend to give and receive different amounts of appreciation? Wikipedians have often asked this question in our discussions about doing research together. To find this out, we analyzed the total historical number of Thanks sent and received by accounts that experienced appreciation in any way during the year before June 1st, 2018. We observed three types of Wikipedians:

- Editors who received Thanks and never thanked others

- Editors who gave Thanks but never received thanks

- Editors who gave and received Thanks

For example, all three groups are present in the following chart from the Persian Wikipedia. Over twelve months, 847 Wikipedians received but never sent thanks, 1102 thanked others but were never thanked themselves, and 749 Wikipedians both sent and received thanks.

Like Persian, every language Wikipedia includes these three kinds of editors. In the next chart, we show the same illustration for all 27 languages we analyzed.

Studying Your Questions About Appreciation on Wikipedia

We're excited to work with Wikipedians over the next year to make shared discoveries about appreciation and other issues that matter to communities. What does that look like?

In the past two years, CivilServant has worked with communities of millions of people on Reddit to test ideas for preventing harassment in discussions of science, managing misinformation in news discussions, and reducing conflict in political discussions. Each time, we designed studies together with communities in a transparent process that prioritized ethics and privacy. After each study, we freely share our results. By asking questions that matter to communities, we also make scientific discoveries about human behavior that would be more generally informative outside Wikipedia (read more about our Wikipedia projects).

We're just getting started, so if you and others on your language Wikipedia are interested in working with us, please contact us. And if you have questions or hypotheses about Thanks and Love – what their impact is or how they are used – let us know so we can try to answer them too. We are excited to hear from you!