“observatory1″ by Beach650 is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

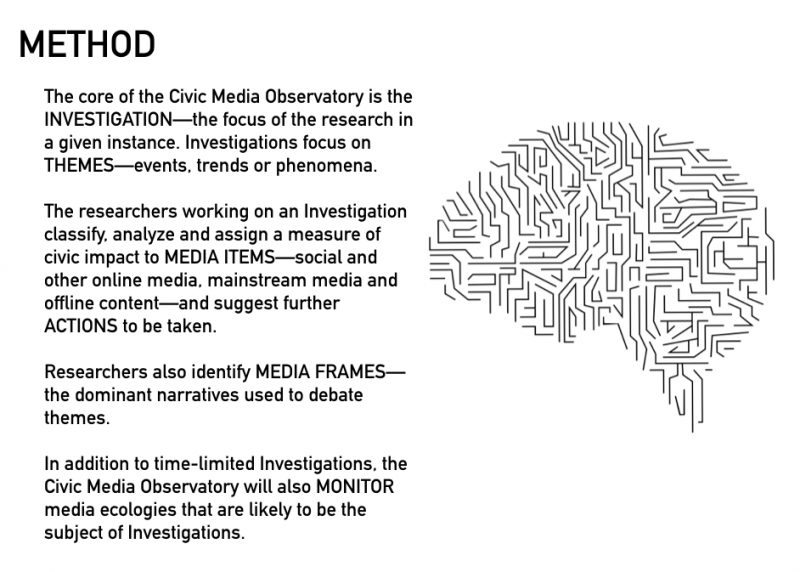

In 2019, Global Voices launched a method for describing and analyzing the media ecosystems that we study. We’re calling it the Civic Media Observatory, and we’re using it to identify and track key subject themes and narrative frames that emerge around events, trends and other phenomena. Our work in the Observatory is focused in part on questions of misinformation, disinformation, disruption and confusion, but our larger goal is to help us to also identify integrity in media in given contexts, and around specific events and trends.

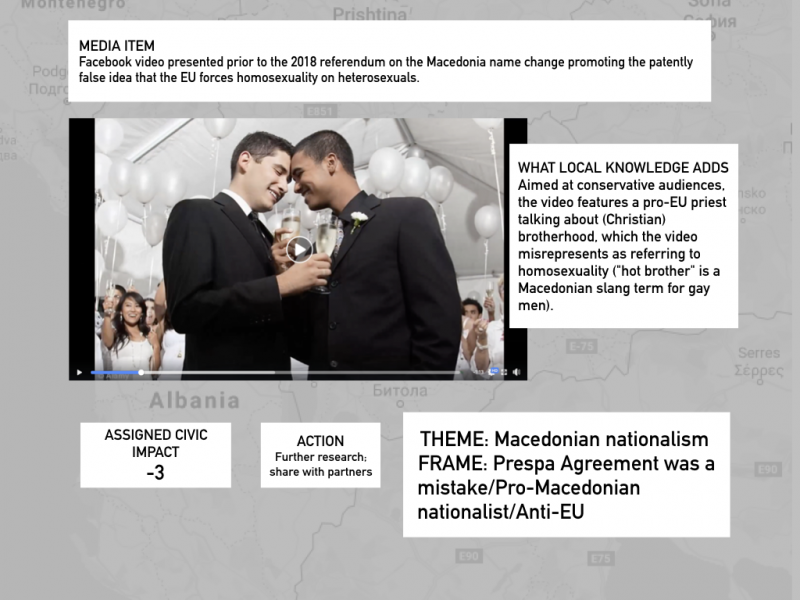

A key premise of all Global Voices’ work is that contextual, local knowledge of the media environments we study can help readers better understand communities and cultures other than their own. When we decide to share a link or write a story, we ask ourselves what information would be helpful for others to evaluate and absorb the given subject matter. Information, after all, does not exist in isolation from cultural, linguistic, and political environments. Learning how to read circumstances, and knowing which contextual and subtextual information to unpack is a key element in any journalistic act that seeks to translate ideas across cultures, languages, and localities.

Our work in the Observatory is focused in part on questions of misinformation, disinformation, disruption and confusion, but our larger goal is to help us to also identify integrity in media in given contexts, and around specific events and trends.

Every good Global Voices story helps us to see those local markers of meaning, and to get a bit closer to the story we’re discussing. That’s true whether we’re talking about a curious meme in which young Taiwanese models suddenly all make the same hand gesture on their Instagram posts, if a Macedonian political figure shares a quote from Nostradamus on Facebook, or if Ethiopian video bloggers discuss a fistfight in Washington D.C.

Over time, as we explore the many ways in which we understand local online conversations, social media feeds, videos, and journalism, we start to notice patterns: how images attain symbolic meaning, then spread and shift as contexts change and new groups take up ideas; how certain words become the locus for political disputes. We see narrative patterns that are larger than a single story, and notice that the underlying assumptions of different communities shape and frame narratives using encoded images, insider language, metaphor, allegory and other tropes.

Global Voices has periodically designed and run projects that explore these narrative patterns, looking at relationships between writers, link densities, word frequency and adjacency and other clues to narrative formation. We’ve also built numerous qualitative data sets, in which we define categories that are useful for identifying patterns. Projects such as the Technology for Transparency Network, Threatened Voices, our research on Facebook’s Free Basics, and Newsframes have helped us to understand the movement of ideas through cultures and across communities.

We are looking at a full range of stories, memes, artifacts and objects that make up the media, whether that’s in a mainstream news story, a social media feed, an online video, a commerce website, a poster stuck hung at an intersection, or graffiti tagged on a wall. We explore the fluidity of media in our networked, mediated age, knowing that a banner on the side of a building can be photographed, uploaded to a social media site, and then spark a conversation that ends up becoming the subject of a news story, and then a debate in a parliamentary hearing. This fluidity is a byproduct and a hallmark of the leveling effect of placing all media as “objects” in digital ecosystems, where they can be shared, altered, annotated, recontextualized, and redefined.

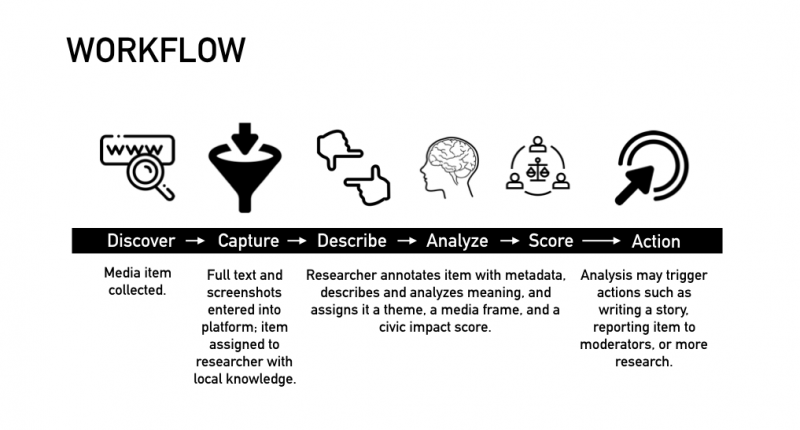

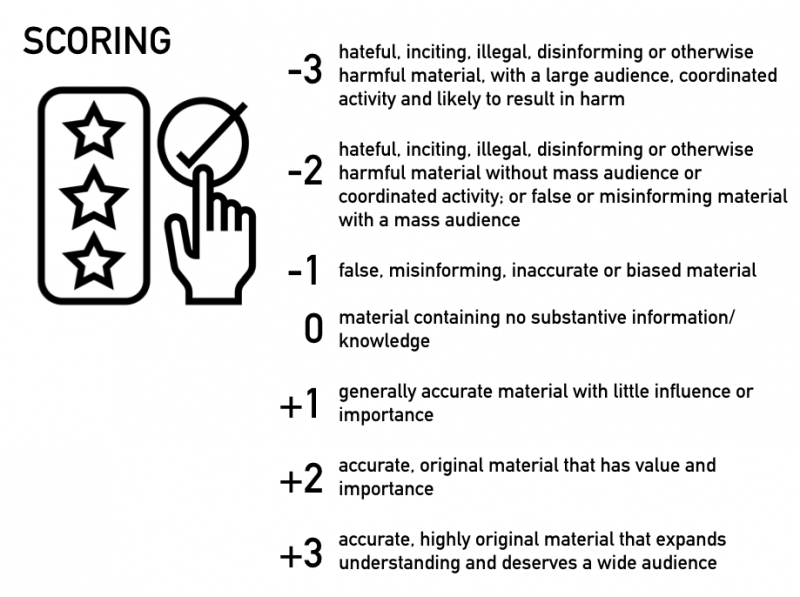

Above all, the observatory is a way for us to standardize the questions we ask of the media items that we study. With those questions we attempt to explain the civic value of our media, and suggest actions that we might take in response. The standardization of our questions helps us to compare these media items, both within a given investigation and over time, across different investigations and media environments. This practice echoes the leveling function of online environments, in which all media objects are subject to taxonomies to order, search and annotate, as well as the folksonomies emerging in our social media that appear as hashtags, search terms, and other socially defined markers of meaning.

Our hope is that by standardizing analysis, we will help to move recent conversations about the value of online media and the internet away from the all-to-frequent question of whether something is good or bad, true or false, information, misinformation, or disinformation, and explore the many ways we create, absorb and understand information.

The observatory process is conducted by teams. This gives us feedback, opportunities to test and compare our assumptions, and forces us to ensure that the descriptions and analysis that we’re putting forward are being tested for comprehension by our peers. The observatory is a social process, in which the learning of the team is also a goal. It is, in other words, also an exercise in literacy.

For each observatory instance, we create an investigation with its own parameters subject matter, and duration. Our pilot investigation was an exploration of possible EU accession, which you can explore in more detail in the presentation below: