Welcome to Global Voices!

We’re thrilled that you’re interested in writing for us. This comprehensive guide will get you started. Global Voices (GV) approaches news reporting a little differently than most news outlets. Since we are focused on promoting underrepresented citizen voices, most of our stories have a unique angle or perspective that you won’t find in most mainstream media outlets. Let us show you what we mean, and how to create a GV story!

This starter guide will help you write stories that are accessible to readers around the world. To see our style guide, which details all of our grammar and editorial rules, click here. To see our posting guide see here.

News writing

We want GV stories to be well-sourced, accurate, and clear, as well as accessible to a global audience. GV stories should adhere to professional news writing standards. Our experienced editors work with writers to ensure their articles meet all GV standards.

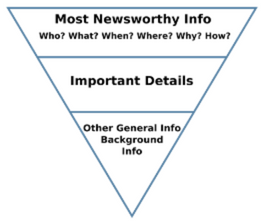

The Inverted Pyramid

Inverted Pyramid. Graphic from Wikipedia (CC0 1.0)

When writing a story, you should try to answer the five Ws at the very beginning. The five Ws are:

- Who: Who are the key characters in a story?

- What: At the most basic level, what is the story about?

- When: When did the events in the story happen?

- Where: Where did the story take place?

- Why: Why is this relevant to the reader, region, and wider context?

It’s sometimes useful to add “How?” to that list as well. In this structure, called the “inverted pyramid,” the story starts with the most essential and interesting information while supporting details follow in subsequent paragraphs in order of diminishing importance.

The Lead

The lead (or lede) is the first 1-2 sentences of an article and is the most important element of a news story. It should hook readers and convey the main idea. The lead is often followed by a nutgraph — a concise paragraph that gives an explanation of the story and why it matters in a nutshell.

When writing a lead try to start with the most important information. Do not start with a date or time, as that is often less important than other information such as who is involved and what happened.

Ex. Brazilian riot police violently evicted a group of indigenous people from a former museum they had occupied in Rio de Janeiro to make way for the 2014 World Cup construction.- Brazil Violently Ousts Indigenous Village Ahead of World Cup

Ex. As the tragedy surrounding attacks on churches and hotels unfolded in Sri Lanka on Easter Sunday, the Sri Lankan government took the unusual step of preemptively blocking a range of social media sites. – Government actions in Sri Lanka Easter bombings raise the question is social media helping or hurting

For more detailed advice on writing leads, read Tips for Writing Leads.

Types of Leads

Direct Lead:

Direct leads immediately explain what the main idea of the story is. Also known as hard news leads, they answer the who, what, where, when, and why of a story right from the start.

Ex. Some academics say Shakespeare was a ruthless businessman who grew wealthy dealing in grain during a time of famine. – Study shows Shakespeare as a ruthless businessman from the Tampa Bay Times

Delayed Lead:

Delayed leads introduce the story to the reader in a more creative way. This could be an anecdote of some kind of playful description or language. A more detailed explanation should follow immediately after to explain how the lead is relevant to the story.

Ex. Hoarder, moneylender, tax dodger — it's not how we usually think of William Shakespeare. But we should, according to a group of academics who say the Bard was a ruthless businessman who grew wealthy dealing in grain during a time of famine.

Researchers from Aberystwyth University in Wales argue that we can't fully understand Shakespeare unless we study his often-overlooked business savvy. – Study shows Shakespeare as a ruthless businessman from the Associated Press

Concise Sentences

Try to keep paragraphs between one to three concise sentences.

If you are unsure about sentence length, read the sentence out loud at a relaxed pace in a single breath. If you can't finish the sentence easily, you may want to break it up into two or more different sentences. Remember most GV stories also get translated into other languages, and translators will appreciate shorter sentences. So we want to feed the story to the reader in short, digestible bites — give the reader too much information, and they will choke.

Active Voice

Most of the time, it is better to use active voice instead of passive voice in your writing. This way, we keep people as the focus of our posts and not the events that happen around them.

PASSIVE: The meeting was protested by angry residents.

This is passive. The meeting is the subject of the sentence instead of the protesters.

ACTIVE: Angry residents protested the meeting.

This is active. The protesters are the subject.

One important exception to this rule is when writing a lead involving legal processes, crime, injuries or death. In these cases, sometimes we prefer passive voice in order to keep a person as the focus of the lead.

ACTIVE: National police arrested a prominent blogger known for his ruthless exposés of government waste on charges of tax fraud.

Not bad, but police share the spotlight with the blogger in this lead.

PASSIVE: A prominent blogger known for his ruthless exposés of government waste was arrested on charges of tax fraud.

The blogger is now the sole focus of the lead.

It all depends on who should be the main focus of a lead. Also always consider who you are centering in your sentences.

Avoid Jargon

News style is obvious and precise. For our content to be easily understandable to a global audience it must be jargon-free. All specialized language or slang should be explained.

No Opinions

Authors must keep their personal opinions out of stories. We call this editorializing. All statements and perspectives should be accompanied by evidence that supports the claim.

We don't normally write first-person narratives; our authors rarely use ‘I’, ‘me’, ‘us’ or ‘we’ and all stories, with a few concrete exceptions, are written in the third person.

Sourcing

At GV, we rely on trusted citizen media, local or independent sources to back up our facts. Any time the information in your story comes from a source, and not you, it should be attributed, regardless of whether that information is a direct quote or not. While it is good to find a source in English, when not available, consider other languages relevant to the story. A good rule of thumb is to attribute once per paragraph. This may seem repetitive, but it’s important for our authors to be clear about where their information is coming from.

Sourcing with hyperlinks is essential in the quotes we use from social media, citizens, and local media to support our writing. Whenever you quote, blockquote or reference a blog or media channel in your post, provide a direct hyperlink to the source. Try to hyperlink only a few words, don't hyperlink whole sentences of text.

Some helpful sources as you begin to write your own GV story:

- Previous GV articles

- Human Rights Watch

- Amnesty International

- UN human rights office

- Freedom house

- Reporters without borders

- Regional human rights watchdogs

- Greenpeace (env stories)

- Mongabay (env stories)

- International criminal court

First-Hand Reporting

We are mostly a second-hand reporting site — we curate from sources that live on the internet — but sometimes we do engage in first-hand reporting. And whenever we do, we try to overemphasize that this is a case of first-hand reporting through clear attribution.

In cases of first-hand reporting, where the interview was conducted over email, phone, Skype or in-person and there aren’t any public digital files to back up attribution, we encourage authors to make attribution transparent and clear by adding language that explains how, where and when the interview was conducted. Examples:

Ex. I conducted this interview in person with Navi Lagis.

Global Voices conducted an email interview with Ali Omar.

Speaking with Global Voices on Skype, Ali Omar said […]

Read our guidelines for conducting first-hand reporting.

Story Structure

The standard GV story contains the following elements: headline, lead, context, citizen or social media commentary, photo and/or video, closing and excerpt.

We also do basic photo posts, interviews, video posts and podcasts; these stories always have a headline, lead and context.

To save time for readers, authors, editors and translators, the word limit for our stories is 1,000 words. There can be exceptions depending on the story; speak to your editor if you would like to write a longer post.

Headline

Headlines should give readers a general idea of what the story is about or why it matters. They should be catchy and interesting, but also as relevant and descriptive as possible. Good headlines are never dull; they are often emotional and create a vivid mental picture of the story. Be sure to include a location (country, region, city, etc.) that is familiar to most readers.

In general, headlines should not exceed 15 words. Please be aware that editors may change headlines to ensure they are clear to the maximum number of readers. It is helpful to brainstorm headlines with your editor to get the very best one possible. Only the first word and proper nouns should be capitalized in headlines.

Ex. How a swimming pool became Puerto Rico's symbol of climate change and corruption

Ex. Will the Indomitable Lionesses of Cameroon ever roar again on the football field?

For more detailed guidance on writing headlines, read Tips for Crafting Headlines or How to Write Headlines That Work

Subheadings

GV uses subheadings to separate stories into organized, manageable sections. Please consider 1–3 subheadings that you can use to divide your story.

For example in this story Australia's iconic Kosciuszko National Park faces threats on two fronts about legislation that might threaten a national park in Australia, we separated the piece into 3 sections: The intro which lays out the conflict, subheading 1: Economic development; and subheading 2: Wild horse control

Subtitles within the story should be in “Headline 3″ font case. You only need to capitalize proper nouns in section subheadings.

Context

Context explains to our readers why the information we are giving them is important. We should assume that readers are unfamiliar with the topic we’re writing about. According to Journalism Professor and Media Critic Jay Rosen, for news stories, there are three types of context.

Important context should be included near the top of our stories instead of buried near the end. Imagine someone from the other side of the world reading your story. Explaining right away why the story matters and/or how it fits into the bigger picture is part of what will hook them into reading the rest of it. If the reader is left asking “so what?” at the beginning of a post, they might give up on it.

Background Knowledge

This encompasses the things you need to know to “get” why the story is news. This can be achieved by briefly explaining and linking to an explainer article or Wikipedia entry. For example, in our coverage of Bangladesh's Shahbag protest demanding capital punishment for war criminals we included an explanation on and Wikipedia link of the 1971 Bangladesh's Liberation War, which is when the atrocities were committed:

Ex. It is not only Bangladeshi men who are occupying the capital city Dhaka's Shahbag intersection demanding capital punishment for war criminals.

The protests have seen extraordinary participation by women. Students, working professionals, and mothers accompanied by their young children have all lent their voice to the Shahbag protests, a movement spearheaded by bloggers and online activists, seeking the death penalty for those who committed crimes against humanity during the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971.

An estimated 200,000 to three million people were killed by the Pakistani army and approximately 250,000 women were raped during the war.

Commentary

We include citizen media commentary from blogs, forums, and social media sites such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Weibo, and Mastodon. No matter the source, there are a few basic things to keep in mind when selecting commentary:

For more information on how to format social media content, please refer to the Posting Guide.

Don’t share from private social media accounts

There is an ethical perspective to consider when sharing social media posts. Many people still don't realize that their images and content may be taken and used in a news context. You may need to consider the implications of including an individual's name and comments in a story. Will it put them in danger or affect them at all?

A good rule of thumb is to only use content that is freely available in the public domain, i.e., that can be viewed by anybody and is not restricted to the individual’s friends. Always try to link directly to the comment or comment thread.

Some posts should be anonymous to protect the user. In these cases, try to give a little context if it will not impact the user.

Ex. @anon_China, an anonymous Twitter user from Kunming province, China, tweeted on Friday, March 18:

Avoid including many quotes that say the same thing.

The selected commentary should show a range of opinions on a topic. You can paraphrase a repeated sentiment.

Ex. @alpha, @beta, and @gamma were unanimous in their view that Global Voices is the best website in the world.

Explain who the user is.

If they are a well-respected blogger, area expert or media professional, mention that in the text leading into the quote. This establishes their credibility as a source. We must be clear about any agendas that users may have. This will alert readers to take what they say with a pinch of salt. Opt for users located in the country where the event is taking place or people whose accounts focus on the area or topic being discussed.

Explain why that particular point of view is relevant.

A basic rule of news writing is to never assume that readers know something you haven’t explicitly told them. We need to put all the important information on why a point of view matters right there in the post, so readers can figure out how it fits into the bigger picture.

Add context.

Explain any terms, references or slang in the tweet that our global audience might not understand. Mention if the commentary was in response to another comment, story or event, appeared on a certain page or group, or coincided with a certain event or date.

Be selective.

Instead of including a lengthy selection of a social media publication in a story, it's a good idea to only quote the most relevant, witty or to-the-point part and paraphrase the rest. That way, we tighten our stories and avoid repeating any information unnecessarily.

Avoid copy-pasting commentary one after the other.

Don't overload a post with commentary after commentary, with only a “This person wrote:” followed by “And this person wrote:” between them. Citizen commentary should move the story along with purpose, not simply be there because it's expected.

Always include the original commentary.

Don't include retweets or shares. We should always use the original source in its original form. Remember a blockquote in the original language should be immediately followed by its translation. More details in our Verifying Citizen Media guide.

Always check the post in “preview” mode of WordPress.

Occasionally, a post will look odd or be cut off when it is officially published. This is especially true of open-source social media outlets or smaller/newer sites that are still working out technical kinks. To prevent this, always check the post in preview mode of WordPress. You should make sure the post is fully visible and centered.

Inline Quotes vs. Blockquotes

Short, direct quotes can be enclosed in either double “…” or single ‘…’ quotation marks, depending on whether you use UK or US spelling and grammar. Lengthier quotes should be enclosed in a blockquote tag on its own line.

Consider alternating blockquotes with inline quotes to avoid the visual eyesore of blockquote after blockquote, which can be overwhelming at first glance.

Always provide hyperlinks for direct quotes if the quote is taken from someplace that is available online.

Multimedia

Images

All stories should have a big, beautiful image at the top. Image captions are brief descriptions that usually appear underneath a published photo. Like headlines, captions should be concise, precise, and visual, explaining to the reader what is not obvious about the photo. Captions should also include copyright information and a hyperlink (if screenshotted from a YouTube video) Captions should try to answer the following questions:

- Who is in the photo?

- Why is this image in the post?

- What is going on?

- When and where was this?

- Why does he/she/it/they look that way?

- How did this occur?

Ex. A woman displays her ink-stained finger after voting in Cairo, Egypt on 9 Nov. Egyptians took to the polls today for the first round of parliamentary elections. Image by Flickr user @adam101 (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Check out this column in The Guardian to learn more about the importance of photo captions as well as this International Journalists’ Network article with tips on how to write better captions. For more information on the technicalities of inserting photos, please refer to the Posting Guide.

Video

When embedding videos in a story, please remember to include:

- An explanation of who uploaded the video and where

- An explanation of what the video shows

- A link to the video

We can't assume that readers will watch a video embedded in a story, especially if it is more than a few seconds long. Videos are sometimes deleted after we include them in a story, too. To ensure readers have the information necessary to understand a story now and in the future, we need to explain what happens in the video and quote any important dialogue (and, if necessary, offer a translation of dialogue).

For example, the story “VIDEO: Student Film on Japan's Ruthless Job Hunt Goes Viral” explains what the student film shows:

Ex. Finding a job in today's tough economy is hard. But for Japanese college students, the country's ultra-competitive recruitment process or “shu-katsu” which starts a year or more before graduation, takes things to a whole new level. “Recruitment Rhapsody,” an emotional short animated film that captures the rigid and obstacle-ridden job hunt process Japanese students must endure, has gone viral with more than 350,000 views.

The film by art student Maho Yoshida was uploaded to YouTube on March 9, 2013 and illustrates a regular carefree university student who suddenly finds herself struggling to find a job among a crowd of focused, competitive, and uniformly dressed sycophants.

For more information on how to embed videos in a post, please refer to the Posting Guide.

Closing

Sum up your post with a big picture closing. What do you want the reader to feel when they finish the post? Should they have a sense of how big the problem is? Or should they feel hopeful? Make sure your last few words speak to them.

Excerpt

All stories should contain an excerpt that entices the reader to click and read. These excerpts appear on the homepage under the headline and next to the photo. They also appear on social media sites like Facebook when someone posts a link to the story.

Excerpts should not repeat the headline or lead. For more on excerpts, see Tips for Writing Tempting Excerpts.

News Writing Checklist

A useful writing checklist to go over before writing your Global Voices story for review:

- Don’t write in a stream of consciousness: When you draft your story, the inverted pyramid will be your best friend. The structure will allow you to give the reader a solid idea of the story in the first few sentences, and provide relevant supporting information afterwards.

- Get it right: If you don’t have facts, you don’t have a story. Take your time to get the facts straight. If you don’t know the answer, find it from a reliable source and verify the information.

- Name your sources: When you name sources, you lend credibility to your story. Be aware that in certain situations such as reporting on persecuted communities, identifying a source by their full name might put that source in harm's way.

- Be fair: Go to great lengths to get information from all sides, even if you personally don't agree with them. If one side is unwilling to talk or hasn't publicly commented on the issue, say so in your piece. At least you tried.

- Be civil: Avoid getting personal in your story. If it’s not relevant to the story, don’t attack the character of another individual.

- Avoid conflicts of interest: If you have a close tie to a source or organization in your story, let your audience know. Don't blur the line between promotional material and news. And no matter how small, don’t accept gifts.

- Don’t plagiarize: Don’t steal content from someone else. You wouldn't like it if it happened to you. Give the story a unique spin by putting things in your own words.

- Find your voice: The internet is full of content, so you have to find a way to stand out from the rest. Be original, be interesting and be relevant.

- Keep good records: Make sure you document where and how you found information. Your editor may ask for proof of your excellent reporting.

- Never stop learning: No matter what stage of life or professional development you are in, you can always improve as a writer and researcher. Take courses, read lots, and ask questions.

- Have fun: Researching and writing a story for Global Voices should be a positive experience. Write about something that interests you and have fun with it. Your readers will thank you for it.